Secrets of Dumbledore: Dumbledore’s Wand and Wulfric of Haselbury

by Dr. Beatrice Groves

Today is Wulfric of Haselbury’s day – the saint after whom Albus Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore is (in part) named. Harry Potter is full of saints’ names, and these names always carry some kind of hint about the character who bears them (This kind of naming is called cratylic naming, and it is perhaps Rowling’s favorite literary device.) Hedwig, for example, is probably the most important saints’ name in the series, and the Sisters of St. Hedwig were established to educate orphan children. Harry’s owl’s name touchingly conveys the way in which Hedwig cares for her owner, not just (as might be expected) the other way around. Percy Weasley’s middle name (Ignatius) suggests that like Ignatius Loyola – a saint who underwent a famous conversion – he might switch sides. Then there is Binns’ Christian name: Cuthbert (a name Rowling gave him when planning the series, although it was not included in the final text). St. Cuthbert, a historically significant (and deeply uncongenial) saint, is a perfect namesake for an unsociable history teacher. Rowling has noted how Binns was based on a university professor whose “disconnect with his students was total,” and St. Cuthbert, too, was famously unenamored of those who came to him in the hopes of imbibing some of his wisdom.

The Clerk of Oxford’s superlative blog on Anglo Saxon England and the liturgical year tells us that Wulfric of Haselbury (who died on this day in 1154/5) was “an anchorite who lived in a cell attached to the church in the Somerset village of Haselbury Plucknett. He was noted for his miracles of healing and prophecy, and though he was never canonized, pilgrims were still traveling to his shrine at the time of the Reformation; tales about Wulfric were collected in oral tradition in Somerset as late as 1900.” Wulfric’s gifts of healing and prophecy align with Dumbledore, as do his linguistic abilities. Dumbledore is a gifted linguist (able even to speak Mermish), and when Wulfric heals a mute man, the newly vocal man is rather surprisingly bilingual (adept at French as well as English).

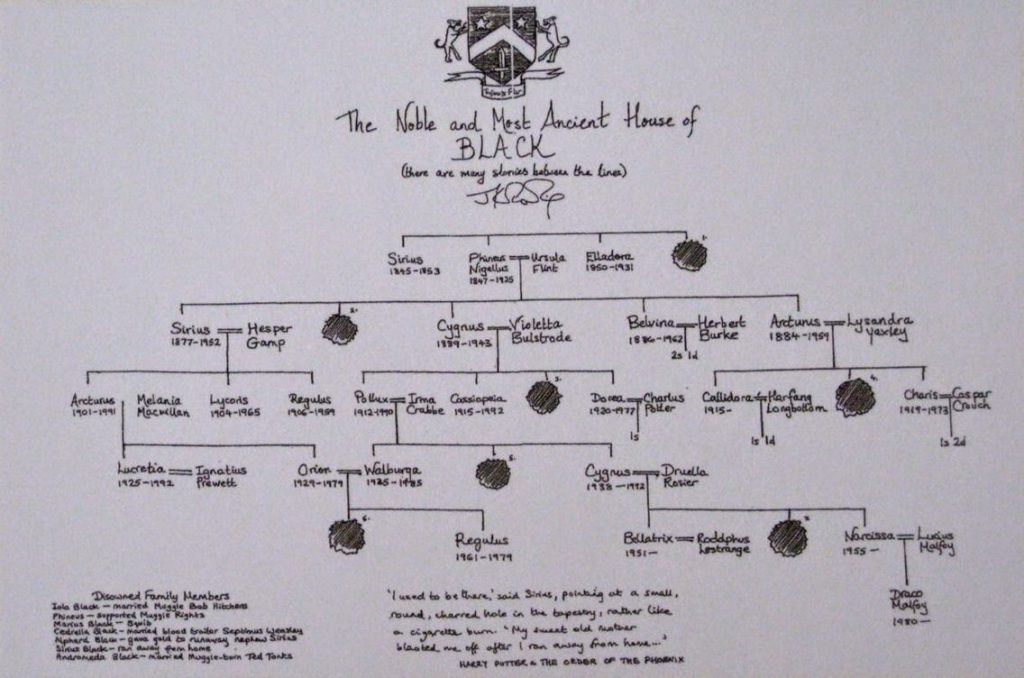

Handwritten Black Family Tree

Rowling has used another little-known saint from South West England as a name source (Walburga, an 8th century Devonshire Saint who turns up on the Black family tree), and it seems likely that she knew of both Wulfric and Walburga because they were relatively local to her growing up in Tutshill (or when at Exeter University). Wulfric’s fabulously named home village of Haselbury Plucknett is in Somerset, and many South West placenames – such as Porlock, Dursley, Chudleigh, and Ottery St. Mary – appear in Harry Potter transformed into animals, cousins, Quidditch teams & the Weasley’s home village of Ottery St. Catchpole.

Rowling is likely to have known of Wulfric because he was a relatively local saint, but it remains a very unusual choice for a name. And it seems to be possible that she chose it for him because Dumbledore was born on, or near, Wulfric of Haselbury’s day on February 20. And this is a tempting possibility for another reason.

I must admit, I always wondered why nobody ever asked me what Dumbledore’s wand was made of!” (J.K. Rowling)

The answer to this question, of course, turned out to be crucial for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – but Dumbledore only owned the Elder Wand after winning it from Grindelwald in 1945. Which has led me to wonder if this question will once again turn out to be important in Fantastic Beasts?

Enter Robert Graves – a celebrated poet, novelist, classicist, and author of an influential “Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth” called The White Goddess (1948), which has never been out of print. Graves’s father, incidentally, was Alfred Perceval Graves; and his nephew was Richard Perceval Graves – a family naming trait that is certainly the source for Percival Graves’s name (as well as, possibly, another of Dumbledore’s middle names). In The White Goddess, Robert Graves states that each month of the year is governed by a particular wood and a particular rune, and out of this idea, he created the so-called Ogham Tree Calendar (also known as the Celtic Tree Calendar). Graves based this calendar on the arboreal sources of some rune names, but he extended this, as well as inventing the link with months to create a more satisfying and complete schema. The Tree Calendar he thus devised has proved immensely popular, and among its other influences, it is the basis of some aspects of wandlore.

Rowling used this calendar to choose some of her character’s wands by aligning these wand woods with their birthday tree according to the calendar. On March 16, 2006, in the lead up the publication of Deathly Hallows (in which we were to learn about the importance of the Elder Wand for the first time), Rowling posted extensive information about how she had used this calendar for assigning wand woods. If Dumbledore’s birthday were to fall on February 20, according to this calendar, he would have an ash wand. But, as Rowling has said, she does not stick to this tree calendar so much as take inspiration from it – and I am particularly interested in the tree that falls just before (February 17): the rowan.

In traditional folklore, the rowan is one of the most explicitly magical trees. It is said that its old Celtic name fid na ndruad means “Wizards’ tree,” and it was regularly used for defensive magic. Cradles were made of rowan to protect against changelings and the famous exclamation in Macbeth “Aroynt thee witch” may derive from the idea that rowan trees (“rauntree”/“aroynt thee”) had virtue in deterring witches. Rowan’s power meant that it was also used for fashioning protective crosses (such as those on display in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford). In one of the most atmospheric Oxford fantasy novels – Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising (which certainly influenced Harry Potter) – the wooden Sign which will repel the forces of the Dark must be made from rowan: “our wood is one which the Dark does not love. Rowan, Will, that’s our tree. Mountain ash. There are qualities in rowan, as in no other wood on earth, that we need.”

The Christian iconography of rowan crosses – both historically and in Cooper’s novel (her Signs are crosses within a circle) – is peculiarly suitable. For, until the nineteenth century, rowan was known in English as the “quicken tree” or “quickbeam.” “Quickbeam” is a strikingly evocative name – bringing together the words for being alive (“quick”) and tree (“beam” is Old English for tree, and remains in some modern tree names, such as hornbeam and whitebeam). “Beam” was likewise Old English for the cross, which was so often understood as a tree (“beam-lights,” for example, were lighted candles placed before the rood, or cross, in a church). The connection between these two types of “beam” – the cross and a tree (Acts 5.30) – is part of the typological connection between the Fall (caused by eating an apple from a tree) and Christ’s redemption. This makes rowan’s name of “quickbeam” a peculiarly evocative one – a name that is probably a sign of the belief in the tree’s efficacious qualities. (Tolkien, unsurprisingly, was drawn to the Old English significance of the name “quickbeam” and gave it as a nickname to one of the Ents in Lord of the Rings).

Rowan, or “quickbeam,” therefore, has a uniquely magical and even sacred reputation which makes it all the more surprising that it never appears as a wand wood in Harry Potter. The more so given the fulsome entry on rowan given by Ollivander in the notes concerning wand woods published on WizardingWorld.com. These extensive comments explain how “Mr. Ollivander believes that wand wood has almost human powers of perception and preferences;” and Ollivander has this to say about rowan:

Rowan wood has always been much-favored for wands because it is reputed to be more protective than any other and, in my experience renders all manner of defensive charms especially strong and difficult to break. It is commonly stated that no dark witch or wizard ever owned a rowan wand, and I cannot recall a single instance where one of my own rowan wands has gone on to do evil in the world. Rowan is most happily placed with the clear-headed and the pure-hearted, but this reputation for virtue ought not to fool anyone – these wands are the equal of any, often the better, and frequently out-perform others in duels.”

Ollivander’s lore here, connecting rowan with defensive charms and hence protective magic, responds closely to the historical use of the wood. Both the virtue of rowan wood and its superiority in dueling would make it a suitable choice for Dumbledore, who defeats the two darkest wizards of all time – Grindelwald in 1945 and Voldemort (at the end of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix) – in duels. Ollivander’s underlying point here (that goodness is not weakness but strength) moreover recapitulates what Dumbledore is constantly trying to teach Harry about the power of love: the force that is at once more wonderful and more terrible than death.

Today – as Wulfric of Haselbury’s day – is Dumbledore’s name day. If that marks February 20 as a day that falls near Dumbledore’s birthday, then both the Celtic Tree Calendar and rowan’s inherent capabilities of goodness and strength would make rowan a natural choice for Dumbledore’s original wand. But the main reason for this guess is the nugget of information given to us by Ollivander at the end of the entry for a wand wood of a very different character – elder:

The rarest wand wood of all, and reputed to be deeply unlucky, the elder wand is trickier to master than any other. It contains powerful magic, but scorns to remain with any owner who is not the superior of his or her company; it takes a remarkable wizard to keep the elder wand for any length of time. The old superstition, ‘wand of elder, never prosper,’ has its basis in this fear of the wand, but in fact, the superstition is baseless, and those foolish wandmakers who refuse to work with elder do so more because they doubt they will be able to sell their products than from fear of working with this wood. The truth is that only a highly unusual person will find their perfect match in elder, and on the rare occasion when such a pairing occurs, I take it as certain that the witch or wizard in question is marked out for a special destiny. An additional fact that I have unearthed during my long years of study is that the owners of elder wands almost always feel a powerful affinity with those chosen by rowan.

This seems to me a startingly odd detail given that elder is the most important wand wood of the Harry Potter series, and rowan is never even mentioned.

The only reason I can see for including this fact which Ollivander has so laboriously unearthed “during long years of study” is that it is a hint about a story that Rowling knows but has not yet told. It is a clue that Dumbledore and Grindelwald – two young men who were to feel such a powerful affinity for each other – were respectively those chosen by a rowan and an elder wand.

Dr. Beatrice Groves teaches Renaissance English at Trinity College, Oxford, and is the author of Literary Allusion in Harry Potter, which is available now. Don’t miss her earlier posts for MuggleNet – such as “Solve et Coagula: Part 1 – Rowling’s Alchemical Tattoo” – all of which can be found at Bathilda’s Notebook. She is also a regular contributor to the MuggleNet podcast Potterversity.